I've known Kathi for many years, ever since my husband and I landed in Texas for what turned into a 17 year stay. Kathi was instrumental in nurturing my nascent passion for writing, and then twisted my arm until I went to Vermont College of Fine Arts. Now I'm thrilled to host her here in the very week that TRUE BLUE SCOUTS has been accorded the honor of being on the National Book Award longlist in Young People's Literature - which to anyone who has had the experience of reading this charming novel comes as no surprise.

And if you are a student of literature, Kathi's answer to the second question is a fabulous and thoughtful essay.

Here's my sweet friend Kathi:

Right from page

one of TRUE BLUE SCOUTS I’m convinced that I’m in the depths of an original

“tall tale.” How did tall tales influence this story?

I think that

tall tales as a genre are deeply rooted in regions. I’ve also always been fascinated by the

stories surrounding Big Foot. He’s an

icon of the American south, particularly those areas that are swampy and hard to

navigate. So called photos of him always

make him look like he’s made up of bits and pieces of the swamp with his mossy

coat and huge feet and hands. So, it

made sense to me to build a story around a creature who might actually arise

from the landscape itself.

I know you feel

strongly that there is an American mythology to be tapped/written – could you

please explain what you mean?

Well, I love

literature that has an element of magic to it, and of course fantasy by its

very nature deals with some aspect of the magical. But when we think of fantasy as a genre, we

immediately think of what I call the “European Model.” That is, a fantasy that is based upon a

monarchical governing structure. There’s usually a “chosen one” at the heart of

these tales, chosen not only because of lineage, but also because of some

magical power, a power that has to be harnessed or granted or learned. The notion that a monarch is magical comes

directly from the notion that they are direct descendants of God. It’s that whole Divine Right of Kings

thing—it hardly gets more magical than that.

And so, in a lot of modern fantasy, the basic structure begins with the

notion that a chosen one will rise to power and become the leader of his or her

people, as ordained by a higher power.

(That’s generic, for sure, and overly broad, but it’s useful as a way to

understand the basic underpinnings of fantasy as we think of it).

An American

fantasy doesn’t have that underlying structure.

In a democracy, we don’t have leaders who are pre-ordained. Instead we the people choose our leaders. So, the notion that a person can, via some

magical power, become the ruler or leader of his or her people doesn’t work in

a democracy. Thus, when American writers

turn to fantasy, it often has a distinctly European flavor. Or at least I think it does. Americans still

love princes and princesses. We really

do love the notion of a chosen one. How

great would it be, after all, if God chose our governmental leaders, or if the president rose to power because he

harnessed the magic of a sword and conquered the opposing forces? Democracy is so messy in comparison.

So, the

challenge, to me at least, is to figure out what a distinctly American fantasy

would look like if you stripped it of the notion of kings and queens. I do think that tall tales are good

examples—they tap into the idea of America being bigger and better than

everyone else, and they’re largely designed to have, at their heart, a

character who arises from a “regular” family—one who is not necessarily

high-born or well-bred. They reflect, in

many ways, the American dream: that

anyone can achieve great things by being themselves and working hard.

Mostly, I think

that American fantasy goes deeper than that, or it has the potential of going

deeper in that it comes from the peculiarities of regions. I want to encourage writers of fantasy to

find the magic in their locales. Unlike

fantasy that is largely based upon the Divine Right of Kings, American fantasy

comes out of the landscape, out of the flora and fauna and the sensibilities of

a particular place. It also comes

directly out of the people who live there, and have lived there.

It’s to tap into

the ancient stories that the region has offered up, too. In this regard, Native American stories

should be acknowledged as part of the literary tradition of a place and

time. Just as modern Eurocentric

fantasy owes an incredible debt to the Arthurian legends, so does American

fantasy owe a debt to Native American tales, many of which form the basis for

tall tales—especially trickster tales. The

challenge is to discover them, to acknowledge them, and to weave them into the

fabric of tales to come. I’m no expert on Native American

literature(s), but what I do know about it tells me that it arose from the

experience of living close to the natural world, that the elements themselves

offered up forms of magic that were incorporated into distinct stories. So the task for the modern American

fantasist is to look at the ancient stories of his or her setting, to at least

try to see the magic in the local landscape that has been recognized for

centuries, and to go from there.

Likewise,

legends and tales that have been imported to our country offer up distinct

possibilities for a deeply American form of magic. If you think of the stories of Toni Morrison

and Virginia Hamilton, for example, they tap into the vein of tradition that

came from Africa via slave ships, and then blend those tales with the politics

and landscape of their time, merging them into contemporary tales that

illuminate more fully what it is to be not only African American, but fully

American.

In The Underneath, I studied every story I

could find about hummingbirds. It’s

surprising how many folk tales and legends I found about such a tiny bird. I tried to understand where the magic arose and

tapped into that vein. Does it have to

do with the bird’s quickness, her tiny size, her shape? What is it about the hummingbird that defies

science and offers up the possibility of magic?

When I was

writing Scouts, I kept asking, what

would a creature who rose right up out of the swamp look like? What would he care about? What would matter to him? What experiences might he have had through

the course of history? Just as a Djinn

might rise up out of the dust of the Arabian desert, or a selkie might show up

on the Isle of Man, maybe a swamp man might rise up out of the east Texas canebrake.

You plant some

wonderful seeds in the narrative. I’m thinking especially of the threat, “I’ll

need a boatload of cash,” and the saying, “when pigs fly.” (And how literally

Chap takes these – so kid-friendly!) How much of this comes to you organically

and how much comes with revision?

I would say that

one percent comes organically and ninety-nine comes from revision.

And a related

question: are you a pantser or a plotter?

I think I start

out as a pantser, but once I get my characters established, I turn into an avid

plotter. I confess to being a believer

in outlines. Oh yes, I do believe in

outlines.

And yet another

related question: I love the asides that are little information grabs –

DeSotos, hogs – and that tie so many things together. Did this story unfold in

a linear way? Did you know from the beginning you’d be weaving these pieces

through the story?

A lot of those

little asides were happy accidents. For

example, I had already decided that I would use a DeSoto for the car, largely

because of the hood ornament. I also

knew that I would have a rampaging batch of hogs—my Bonnie and Clyde figures—but

when I sat down to do a little research on hogs, I almost fell on the floor

when I discovered that the first feral hogs came to this continent on boats

under the command of, yep, DeSoto. I had

a lot of happy accidents like that. It’s

one of the joys of writing.

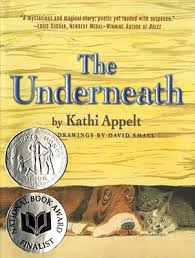

THE UNDERNEATH

and KEEPER are gorgeous stories with serious tone – both made me cry like a

baby. TRUE BLUE SCOUTS made me cry, too, but in an entirely different way, with tears of laughter. What

was it like to “write something funny” for a change?

By now you know that it was Cynthia Leitich Smith

who encouraged me to write something funny.

At first, I didn’t really understand why she would send me a note

telling me that. But it arrived at the

end of a very difficult year for me, and as a friend, she sensed that I needed

to take myself and my whole life a little less seriously. That is a good friend, who has the

wherewithal to tell you something you may not be ready to hear. So, I’ll be forever grateful to Cyn for her

honesty.

And it was

exactly what I needed to do.

I have to say

that I’m a believer in writing what you have to write. That’s not always an easy thing to do. Sometimes it’s painful; sometimes it’s

egoistic; often it’s downright stupid.

But often, it’s what your soul requires.

Cyn is intuitive, and she could see what I couldn’t. I hope that I can be that person for my

friends in return.

Is there a

recipe for sugar pie, and if so can I have it?

You’ll have to

ask Chap or his mother. But if you can

talk them out of it, you have to eat it with a cup of Community Coffee.

Anything else

you would like to share?

Only a big thank

you for inviting me to sit down with you!

Kathi Appelt is the author of the Newbery Honor-winning, National Book Award finalist, PEN USA Literary Award-winning, and bestselling The Underneath as well as the highly acclaimed novels Keeper and The True Blue Scouts of Sugar Man Swamp, and many picture books. She is a member of the faculty at Vermont College’s Master of Fine Arts program. She has two grown children and lives in Texas with her husband. For more information, visit her website at http://www.kathiappelt.com/.

And if I ever find the recipe for sugar pie, I'll share with my devoted readers. Oh, and with Chef Armend Latifi, too.

No comments:

Post a Comment